Article translated by Ken Liu.

This past March, I attended the Huadi Literary Awards in Guangzhou, where my debut novel, The Waste Tide, was honored with the top distinction for genre (SF) fiction. Published in the capital of China’s most developed province, Huadi is the magazine supplement for the Yangcheng Evening News, one of the largest newspapers in the world by circulation (in excess of 1 million). This was also the second literary award my novel has received (after a Chinese Nebula). As a former Googler, I want to invoke the button that rarely gets pressed: “I’m feeling lucky!”

The Huadi Awards was a joint effort by the local government and media, and as one might expect, it was suffused with the trappings of officialdom. Even the ceremony itself was held in a government auditorium. The winners were led on a night tour of the Pearl River, and our hosts excitedly pointed out the splendor of the post-modern architecture on both shores. However, one of the winners, Chen Danqing, a noted liberal opinion leader and artist, reminisced about his childhood visit to Guangzhou in the midst of the Cultural Revolution.

“From here to there,” he said, sweeping his arm across the night, “bodies dangled from every tree.” We looked at where he was pointing, and all we could see were lit-up commercial skyscrapers indistinguishable from those you’d find in Manhattan. “The young are always at the vanguard.”

As the youngest winner among the group—I was the only one born after 1980—I played the role of the eager student seizing an opportunity to learn from respected elders. “Do you have any advice for us, the younger generation?”

Chen Danqing puffed on his cigarette thoughtfully for a while, and then said, “I’ll give you eight words: ‘Stay on the sidelines, hope for the best.’”

I gazed at the reflections of the profusion of neon lights and pondered these eight words. The short voyage was soon over, and the river’s surface disappeared in darkness. I thought there was much wisdom in his words, though the somewhat cynical values they advocated were at odds with the spirit of the “Chinese Dream” promoted by the government.

In the eyes of Han Song, a Chinese science fiction writer born in the 1960s, the Chinese born after 1978 belong to a “Torn Generation.” Han Song’s perspective is interesting. While he is a member of China’s most powerful state-run news agency, Xinhua, he is also the author of extraordinary novels such as Subway and Bullet Train. In these surrealist novels, the order of nature on speeding trains is subverted by events such as accelerated evolution, incest, cannibalism, and so on. Critics have suggested that “the world on the subway reflects a society’s explosive transformation and is a metaphor for the reality of China’s hyper-accelerated development.”

In a recent, widely distributed essay, Han Song wrote: “The younger generation is torn to a far greater degree than our own. The China of our youth was one of averages, but in this era, when a new breed of humanity is coming into being, China is being ripped apart at an accelerated pace. The elite and the lowly alike must face this fact. Everything, from spiritual dreams to the reality of life, is torn.”

As a journalist with Xinhua, Han Song has a broader perspective than most. He points out that the young people who have been grouped into one generation by the accident of their dates of birth hold wildly divergent values and lifestyles, like fragments seen in a kaleidoscope.

My generation includes the workers at Foxconn, who, day after day, repeat the same motions on the assembly line, indistinguishable from robots; but it also includes the sons and daughters of the wealthy and of important Communist officials, princelings who treat luxury as their birthright and have enjoyed every advantage in life. It includes entrepreneurs who are willing to leave behind millions in guaranteed salary to pursue a dream as well as hundreds of recent college graduates who compete ruthlessly for a single clerical position. It includes the “foreigners’ lackeys” who worship the American lifestyle so much that their only goal in life is to emigrate to the United States as well as the “50 cent party” who are xenophobic, denigrate democracy, and place all their hopes in a more powerful, rising China.

It’s absurd to put all of these people under the same label.

Take myself as an example. I was born in a tiny city in Southern China (population: a million plus). In the year of my birth, the city was designated one of the four “special economic zones” under Deng Xiaoping, and began to benefit from all the special government policies promoting development. My childhood was thus spent in relative material comfort and an environment with improved education approaches and a growing openness of information. I got to see Star Wars and Star Trek, and read many science fiction classics. I became a fan of Arthur C. Clarke, H.G. Wells, and Jules Verne. Inspired by them, I published my first story when I was 16.

Not even seventy kilometers from where I lived, though, was another small town—administratively, it was under the jurisdiction of the same city government—where a completely different way of life held sway. In this town of fewer than 200,000 people, more than 3,200 businesses, many of them nothing more than family workshops, formed a center for e-waste recycling. Highly toxic electronic junk from around the world, mostly the developed world, was shipped here—often illegally—and workers without any training or protection processed them manually to extract recyclable metals. Since the late 1980s, this industry has managed to create multiple millionaires but also turned the town into one of the most polluted areas in all of Guangdong Province.

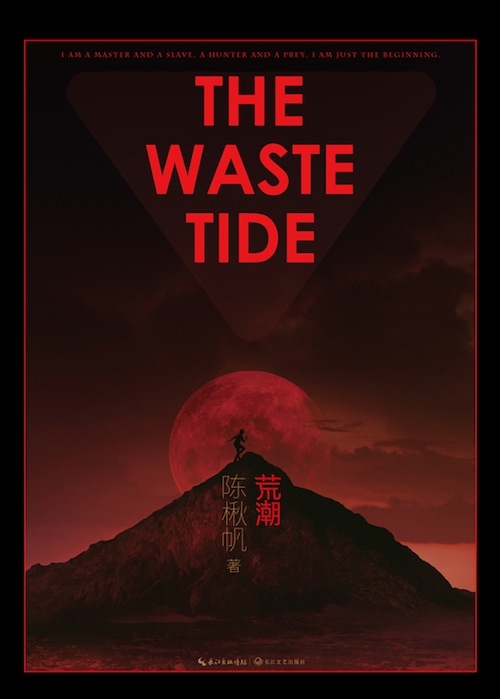

It was this experience in contrasts and social rips that led me to write The Waste Tide. The novel imagines a near future in the third decade of this century. On Silicon Isle, an island in Southern China built on the foundation of e-waste recycling, pollution has made the place almost uninhabitable. A fierce struggle follows in which powerful native clans, migrant workers from other parts of China, and the elites representing international capitalism vie for dominance. Mimi, a young migrant worker and “waste girl,” turns into a posthuman after much suffering, and leads the oppressed migrant workers in rebellion.

Han Song described my novel this way: “The Waste Tide shows the fissures ripping China apart, the cleavages dividing China from the rest of the world, and the tears separating different regions, different age cohorts, different tribal affiliations. This is a future that will make a young person feel the death of idealism.”

In fact, I am not filled with despair and gloom for the future of China. I wrote about the suffering of a China in transformation because I yearn to see it change gradually for the better. Science fiction is a vehicle of aesthetics to express my values and myself.

In my view, “what if” is at the heart of science fiction. Starting with reality itself, the writer applies plausible and logically consistent conditions to play out a thought experiment, pushing the characters and plot towards an imagined hyper-reality that evokes the sense of wonder and estrangement. Faced with the absurd reality of contemporary China, the possibilities of extreme beauty and extreme ugliness cannot be fully explored or expressed outside of science fiction.

Starting in the 1990s, the ruling class of China has endeavored to produce an ideological fantasy through the machinery of propaganda: development (increase in GDP) is sufficient to solve all problems. But the effort has failed and created even more problems. In the process of this ideological hypnosis of the entire population, a definition of “success” in which material wealth is valued above all has choked off the younger generation’s ability to imagine the possibilities of life and the future. This is a dire consequence of the policy decisions of those born in the 1950s and 1960s, a consequence which they neither understand nor accept responsibility for.

These days, I work as a mid-level manager in one of China’s largest web companies. I’m in charge of a group of young people born after 1985, some even after 1990. In our daily contact, what I sense in them above all is a feeling of exhaustion about life and anxiety for success. They worry about skyrocketing real estate prices, pollution, education for their young children, medical care for their aging parents, growth and career opportunities—they are concerned that as the productivity gains brought about by China’s vast population have all but been consumed by the generation born during the 1950s-1970s, they are left with a China plagued by a falling birthrate and an aging population, in which the burdens on their shoulders grow heavier year after year and their dreams and hopes are fading.

Meanwhile, the state-dominated media are saturated with phrases like “the Chinese Dream,” “revival of the Chinese people,” “the rise of a great nation,” “scientific development”… Between the feeling of individual failure and the conspicuous display of national prosperity lies an unbridgeable chasm. The result is a division of the population into two extremes: one side rebels against the government reflexively (sometimes without knowing what their “cause” is) and trusts nothing it says; the other side retreats into nationalism to give themselves the sense of mastering their own fate. The two sides constantly erupt into flame wars on the Internet, as though this country can hold only One True Faith for the future: things are either black or white; either you’re with us or against us.

If we pull back far enough to view human history from a more elevated perspective, we can see that society builds up, invents, creates utopias—sketches of perfect, imagined futures—and then, inevitably, the utopias collapse, betray their ideals, and turn into dystopias. The process plays out in cycle after cycle, like Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence.

“Science” is itself one of the greatest utopian illusions ever created by humankind. I am by no means suggesting that we should take the path of anti-science—the utopia offered by science is complicated by the fact that science disguises itself as a value-neutral, objective endeavor. However, we now know that behind the practice of science lie ideological struggles, fights over power and authority, and the profit motive. The history of science is written and rewritten by the allocation and flow of capital, favors given to some projects but not others, and the needs of war.

While micro fantasies burst and are born afresh like sea spray, the macro fantasy remains sturdy. Science fiction is the byproduct of the process of gradual disenchantment with science. The words create, for the reader, a certain vision of science. The vision can be positive or full of suspicion and criticism—it depends on the age we live in. Contemporary China is a society in the transition stage when old illusions have collapsed but new illusions have not taken their place: this is the fundamental cause of the rips and divisions, the confusion and the chaos.

In 1903, another revolutionary time in Chinese history when the new was replacing the old, Lu Xun, the father of modern Chinese literature, said, “the progress of the Chinese people begins with scientific fiction.” He saw science fiction as a tool to inspire the nation with the spirit of science and to chase away the remnants of feudal obscurantism. More than a hundred years later, the problems facing us are far more complicated and likely not amenable to scientific solutions, but I still believe that science fiction is capable of wedging open small possibilities, to mend the torn generation, to allow different visions and imagined future Chinas to coexist in peace, to listen to each other, to reach consensus, and to proceed, together.

Even if it’s only an insignificant, slow, hesitant step.

Chen Qiufan (a.k.a. Stanley Chan) was born in Shantou, Guangdong Province. Chan is a science fiction writer, columnist, and online advertising strategist. Since 2004, he has published over thirty stories in venues such as Science Fiction World, Esquire, Chutzpah!, many of which are collected in Thin Code (2012). His debut novel, The Waste Tide, was published in January 2013 and was praised by Liu Cixin as “the pinnacle of near-future SF writing”. Chan is the most widely translated young writer of science fiction in China, with his short works translated into English, Italian, Swedish and Polish and published in Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, Interzone, and F&SF, among other places. He has won Taiwan’s Dragon Fantasy Award, China’s Galaxy and Nebula Awards, and a Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Award along with Ken Liu. He lives in Beijing and works for Baidu.

Ken Liu is an author and translator of speculative fiction, as well as a lawyer and programmer. His fiction has appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s, Analog, Clarkesworld, Tor.com, Lightspeed, and Strange Horizons, among other places. He is a winner of the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy awards. He lives with his family near Boston, Massachusetts. Ken’s debut novel, The Grace of Kings, the first in a fantasy series, will be published by Saga Press in 2015. Saga will also publish a collection of his short stories.

What a fascinating article. I’m really glad Tor.com’s getting this kind of thing translated, because there’s no way I’d be able to read it otherwise. (Or even hear about it, likely.)

Thank you, Stanley and Ken for this amazing article. Bookmarking this one for future reference, and checking out Mr Chen’s published works.

Seconding that. The last couple of essays on Chinese science fiction translated by Ken Liu have been a delight to read. Please keep them coming!

great stuff, powerfull and thought provoking

Wow. Thank you for translating and posting this essay. I just read the whole thing out loud to my husband.

Fascinating. I recently read a book of interviews with young Chinese people about these exact topics – Voices of New China by C J Shane. Highly recommended for anyone curious about what day to day life is like for young Chinese people, and how they view their own country.

Thanks all! Really encouraging that you like this piece, and thanks to Ken’s great translation, without his effort we couldn’t make it. If you had any question to discuss, just feel free to mail me via: scifivan@gmail.com.

Looking forward to your feedback!